A new edition of my first book—The Cook and the Gardener—comes out today to mark the 25th anniversary. The story involves a special home, too, so I wanted to share it here as a free post with all Homeward subscribers!

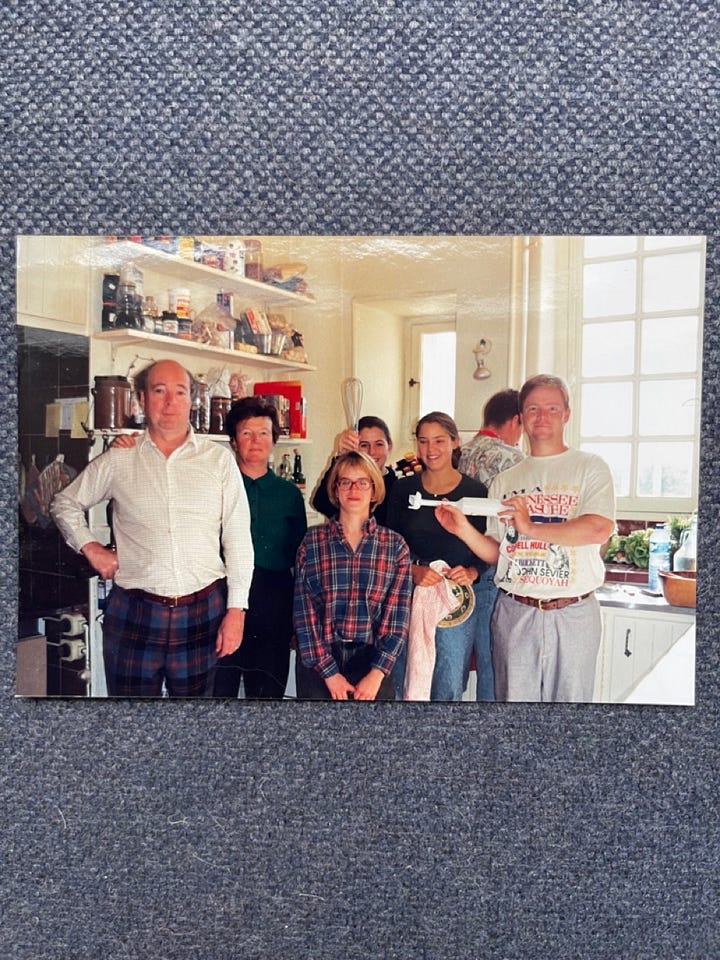

For two years in my early twenties, after baking/cooking my way around Europe, I lived in the Château du Feÿ, in Burgundy, France. The draw? It was home to École de Cuisine LaVarenne, the renowned cooking school started by cookbook author Anne Willan. I didn’t have the money to attend as a regular student, so I joined as Anne’s assistant, which meant that I cooked for her family and worked as an editor and recipe tester on her food writing projects.

Anne eventually closed LaVarenne and sold the chateau. But I went back two weeks ago to see it in its new incarnation. Jessica Angel, an architect from Paris, purchased the property just before the pandemic and has turned the home into a vibrant creative colony/commune and event space. While we walked the grounds, she told me that she hopes that the people with residencies at the chateau leave it changed. That they find new directions in their lives.

That happened to me. When I lived there in the 1990s, I had been working as an apprentice in restaurants and bakeries around Europe, and I wanted to get a proper cooking degree while I tried to figure out whether to become a chef or a bread baker.

Two years and many lumpy soufflés later, I left the chateau with a contract to write my first book: an account of the estate’s gardener, Monsieur Milbert (more on him below), and of cooking seasonally from his kitchen garden. (That book, The Cook and the Gardener, is being reissued today!) A year after that, I was hired by The New York Times and moved to Manhattan. I had found a new and surprising-to-me direction in my life.

I’m a believer, with Jessica, that there’s something transformative about living with others and working together communally in a space. It opens possibilities. It forces you to see alternate ways of doing things (even if it just means that you discover you don’t like doing things in a certain way). Also, as I discovered at the chateau, there’s something freeing about living in a space that’s so old. It belongs to time. You’re simply its guest.

This is not the property’s original chateau; the first was lost, perhaps to fire, and this one was built higher up on the hill in the 17th century. It’s fairly humble by French standards, a handful of outbuildings around what’s essentially a grand country house with a mere–!–15 or so bedrooms.

The chateau’s middling status may be one of the reasons it’s been left largely untouched over the centuries. Grander chateaus get snapped up by wealthy families and fully updated. The Château du Feÿ still has its old stone press, a wide and harrowingly deep well, an abandoned ice house, wine caves, a pigeonnier, and a two-acre walled kitchen garden.

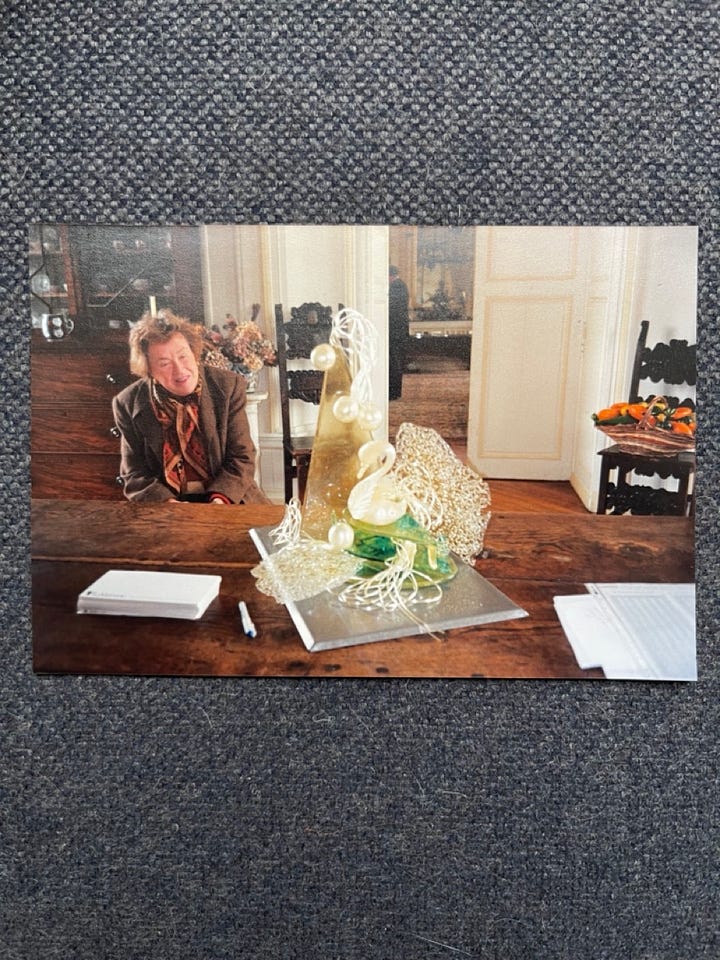

My bosses, Anne and her late husband, Mark, brought a British sensibility to the house after they purchased it in the 1980s, importing floral wallpapers, loads of books (a portion of their exquisite cookbook collection is now at the Getty Museum), and an appreciation for sagging roof lines and worn floors.

I’d been in Europe for more than a year but I hadn’t yet shaken my American lust for the new. A few years before, I’d decided against one potential college because the dormitories were too old, the 19th-century moldings too thick with paint. (I feel shame about this limited view, yes I do!)

This house changed me. Living in a space that had been occupied by so many people over the centuries gave me a sense of my own mortality and quickened my interest in preserving history. Everything there would outlast me. The house made me feel that I should make the most of my time, which freed me to take risks and to make my mark by celebrating what I value. Writing allowed me to do both.

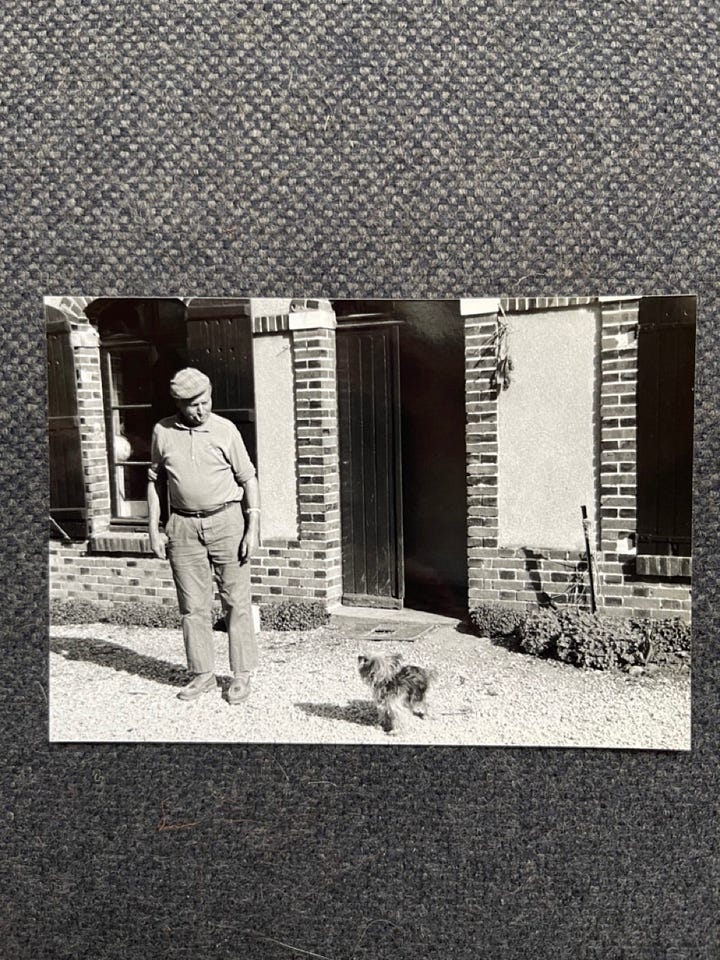

I became enamored with the kitchen garden and its curmudgeonly gardener, Monsieur Milbert. He lived in the space beneath the pigeon house with his wife and their tiny Yorkshire terrier, Puce (“flea” in French). They occupied mostly one small room with a stove, a table, and a TV. Once I got to know them, we’d spend afternoons together watching TF1 news and game shows.

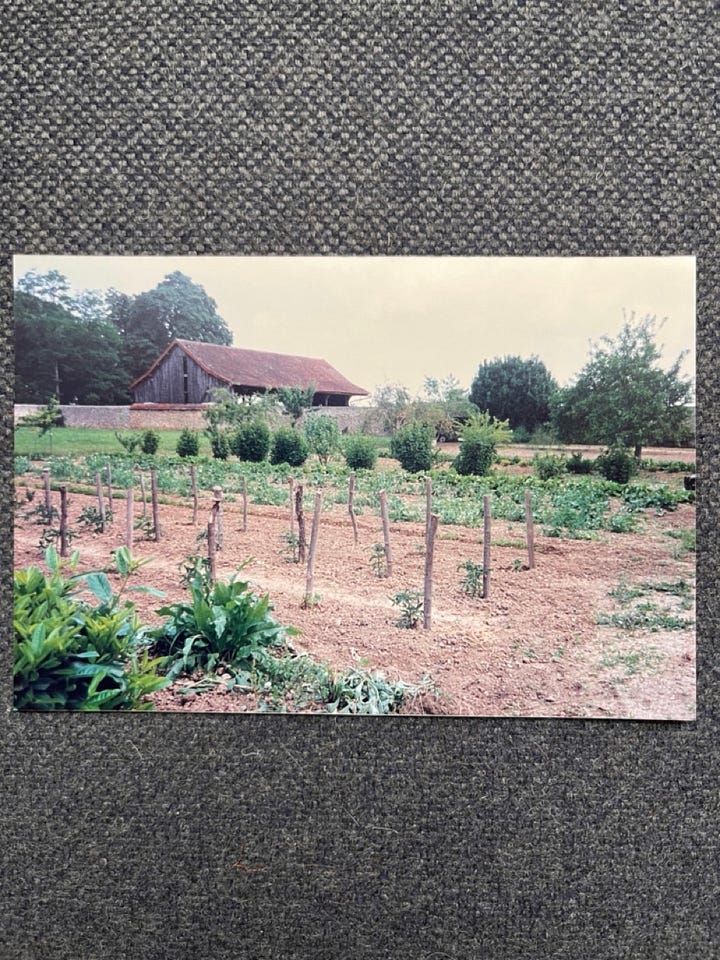

The garden was a wild and magical place with fig and apple trees, gooseberries, zucchini, asparagus, and a few esoteric plants such as medlars and cardoons. M. Milbert rolled his own cigarettes and planted vegetables according to the phases of the moon. He only made use of about half of the available space; he knew his limits and went at his own pace. Still, the garden produced enough fruit and vegetables that by August, we were knee deep in it all. From this, I learned to cook with what it provided, rather than what I wanted. When it was leek season, that was the predominant harvest and I had to make the most of them—marinated with oil and herbs, braised in red wine, and roasted with lamb.

I also learned to live in a house with what it provided, which in this case was peeling paint, slanted staircases, and drafty passageways. I liked how the chateau made you work to inhabit it—I had to build a fire in the library on winter mornings to heat up my work space, and keep the flames going all day. The windows clanged in the wind; the clock on the roof chimed every hour; and you could hear the high-speed TGV train swooshing through the countryside at night. It was a house with its own chorus. I appreciated how the worn concave stone plinth in front of the door reminded me of everyone who’d entered over the years. While I cooked, Anne would sometimes open the liquor cabinet door between the kitchen and living room to say hello. A peekaboo feature that surprised and delighted, like many others on the property.

When I went back to the chateau two weeks ago, after not having visited for more than 25 years, I was struck by how familiar it felt. Jessica has managed to preserve the space while also revitalizing it. The garden is now managed by Guillaume, an energetic and organized young man who has tidied up the tool shed, added a greenhouse, and brought order to a charming but unruly space. Instead of cooks crawling all over the house, now there are artists, founders, and other creative people. There’s a neon sign in the living room that says “Feÿtopia,” the name of the collective. A sonic sphere (a prototype of the one featured at The Shed and Burning Man; one of the creators is Jessica’s husband, Ed Cooke) rests just outside the garden, and a covered structure for weddings (designed by Jessica) sits on the other side of the garden wall. In the right hands, you can fit a lot in two acres.

I also went back to the Milberts’ house. The kitchen and TV area is now a workshop for the chateau’s maintenance person. But I got to explore the bedrooms, which I hadn’t seen before. The Milberts hadn’t seemed like wallpaper people, but there were the remains of some sweet printed wallpapers as you scaled the steps to the pigeonnier.

In my second year there, I designed and oversaw the building of a large, bow-shaped herb garden close to the house; a nod to 17th-century designs. It endures, though not at its best: the decade that the chateau was uninhabited before Jessica bought it left the rosemary, sage, and other hardy herbs in a sorry state. But the walkway is intact, the spirit is there. And Guillaume is working to bring it back and make it his own.

Homes are a way of preserving our existence—and of building on the dreams of others. Understanding this may be the biggest way the chateau changed me. I was lucky to be reminded of this as we embark on our new home.

More from California later this week—à bientôt!

Amanda

The recipes and dishes that are on my mind. This week, I’m sharing my new/old book and a recipe from it that I think you’ll love.

The Cook and the Gardener has remained in print in hardcover for 25 years (given the state of publishing that may be the greatest accomplishment I’ll ever have professionally). Last year, W.W. Norton, my publisher, decided it was time for a refresh for this seasonal cooking staple. So I’m delighted to introduce you to a renewed edition, with a dapper cover, illustrations by Kate Gridley, and a new preface by yours truly.

There’s a chapter for each month of the year so you can cook with the seasons. I wrote this as a young cook so I kept the recipes simple and focused on the flavors of what was coming from the garden. In November that meant Pork Chops Braised with Fennel and Pastis—and at this time of year, it means Rhubarb and Strawberry Confit and this spring salad:

Asparagus with Tarragon Vinaigrette

Serves 4

Ingredients:

1½ pounds asparagus (about 10 ⅜-inch green spears or 5 ½-inch white spears per person), trimmed

Sea salt

½ tablespoon white wine vinegar

Coarse or kosher salt

Freshly cracked black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon chopped tarragon leaves (about 3 branches)

Instructions:

Half fill a large sauté pan (wide enough for the asparagus to lie flat without cramping) with water. Season with sea salt and bring to a boil. Meanwhile, lay the asparagus on the cutting board and cut into equal lengths.

Add the asparagus to the rapidly boiling water and reduce to an active simmer. Cook the spears until they are just tender but still firm when poked with a fork, 3 to 5 minutes, depending on the thickness of the spears.

Drain in a large colander, then spread the spears out on a dish towel to drain off excess water. If you are not serving the asparagus right away or you prefer it cold, have a large bowl of ice water ready and plunge the spears into the cold water to halt further cooking and to cool them off completely before draining.

Meanwhile, whisk the vinegar, salt, and pepper. Add the oil in a slow, steady stream, whisking to emulsify the dressing. Add the tarragon and taste for seasoning.

Lay the asparagus, with the tips all facing the same direction, on a serving plate and pour on the vinaigrette. Serve warm, room temperature, or chilled.

Variation:

Thinly slice ¼ of a preserved lemon and add to the vinaigrette before serving.

The place where I gather my latest finds and late-night research on everything from real estate intel to deep cut shopping sources.

We had a lot of wonderful Poterie Renault, the salt-glazed stoneware from the Loire Valley, at the chateau, as well as ceramics from Gien (which were never my favorite). If you want a French country look, here are some picks from Food52 and beyond:

Manufacture de Digoin (a more modern spin on French country)

Elsie Green has a special section of her site called The French Kitchen, with an extraordinary selection.

Jars’ Réfectoire collection hints at country without being too on-the-nose.

Dear Amanda, I first 'met' you when I stumbled onto your first book, oh those many years ago. Your writing then, and now, astounds. When my husband and I found you the next time, you were writing in the NYT Magazine with your Mr. Latte essays. We have been, and will always be, true fans of yours. To think your twins are now so old blows my mind. Time races on, and we must use each second. Bless you, dear writer.

Amanda - I have loved your first book since it came out. Back then I was an unmoored expat living in Asia, and your tales grounded in the abundance of seasonality, of ancient earth and following the rhythm of moonrises soothed my wariness immeasurably. Then came Cooking for Mr Latte, and your delightful recipes inspired by the bounty of farmer markets lured me back to New York. Around that time I met you briefly when you sat next to me at lunch at Esca; I told you how much I adored you and it happened that you were lunching with your agent!

Fast forward twenty some years… with some sheer twist of fate I come to inhabit an ancient family chateau in the Loire valley that had seen the Hundred Years’ war. In the glorious summer months when we spend time there, I tend to mon petit potager and what book do I have with me? Yours of course! Merci Amanda, merci Monsieur Milbert. Thank you for generously sharing your wonderment, your sensitivities and sensibilities, your wit and wisdom with your readers all these years. Sending you much love and well wishes for this next chapter in your life ❤️❤️